Seyfarth | Pioneers and Pathfinders - Dan Rabinowitz

In this episode of Pioneers and Pathfinders, host Steve Poor sits down wi th Dan Rabinowitz, founder and CEO of Pre/Dicta, to explore how AI and behavioral analytics are transforming litigation strategy. Steve, the Chair Emeritus of Seyfarth Shaw, brings a wealth of experience in leading legal innovation, having pioneered the use of Lean Six Sigma in law and driven Seyfarth’s renowned client service model. His deep understanding of the intersection between technology and legal services makes him the perfect guide for this discussion on how Pre/Dicta is reshaping the way lawyers approach litigation by forecasting judicial outcomes with remarkable accuracy.

th Dan Rabinowitz, founder and CEO of Pre/Dicta, to explore how AI and behavioral analytics are transforming litigation strategy. Steve, the Chair Emeritus of Seyfarth Shaw, brings a wealth of experience in leading legal innovation, having pioneered the use of Lean Six Sigma in law and driven Seyfarth’s renowned client service model. His deep understanding of the intersection between technology and legal services makes him the perfect guide for this discussion on how Pre/Dicta is reshaping the way lawyers approach litigation by forecasting judicial outcomes with remarkable accuracy.

As a former employment litigator and a long-time champion of integrating AI, robotics, and cognitive computing into legal practice, Steve is uniquely positioned to delve into Pre/Dicta’s groundbreaking tools. He and Dan discuss the revolutionary potential of Pre/Dicta’s AI, which leverages data from millions of federal cases to predict litigation outcomes and timelines, offering lawyers a competitive edge in managing risk and litigation strategy. Together, they explore how this innovative technology is empowering attorneys to make data-driven decisions in a way that has never been possible before. Tune in for an insightful conversation on the future of legal practice.

Podcast Summary

Dan Rabinowitz, CEO of Pre/Dicta, shares insights into how AI-driven litigation analytics are transforming the legal field. Pre/Dicta uses behavioral analytics and data science to predict litigation outcomes, focusing on judge-specific patterns, timelines, and case-specific details. Unlike other platforms that rely on generalized statistics, Pre/Dicta tailors predictions to unique case factors, allowing litigators to make strategic decisions regarding motions, settlements, and timelines. This data-centric approach enables firms to reduce litigation costs, improve risk assessment, and offer data-driven client strategies, setting a new benchmark for legal tech.

The conversation highlights how Pre/Dicta empowers lawyers to optimize litigation strategy by integrating machine learning models for motion success rate predictions, timeline forecasting, and legal cost projections. By using behavioral analytics, Pre/Dicta addresses inefficiencies in the legal field, helping firms manage risks and client expectations more effectively while providing actionable intelligence for strategic planning.

Seyfarth | Pioneers and Pathfinders Podcast: https://www.seyfarth.com/news-insights/pioneers-and-pathfinders-dan-rabinowitz.html

Pioneers and Pathfinders: Dan Rabinowitz

Dan Rabinowitz, founder and CEO of Pre/Dicta, discusses the company’s AI tool that forecasts litigation outcomes using behavioral analytics and data science. Pre/Dicta, launched six years ago, provides case-specific predictions and forecasts, differing from other platforms that rely on generalized statistics. The tool analyzes judges’ proactivity, preferences, and biases to predict motion outcomes and timelines. It has been well-received by large law firms, with high usage rates and no help desk requests. Pre/Dicta’s educational component ensures ease of use for attorneys, who can leverage the tool for strategic decision-making and risk assessment.

Action Items

- [ ] Provide a strategy memo to the client on the likelihood of the motion to dismiss being granted or denied.

- [ ] Advise the client on whether to accept an early settlement offer or push for summary judgment, based on the predicted timeline.

- [ ] Explore using Pre/Dicta’s tools to win new business by providing more accurate litigation cost estimates.

Outline

Pre/Dicta’s Origins and Purpose

- Speaker 1 introduces Dan Rabinowitz, founder and CEO of Pre/Dicta, a company that offers AI tools for litigators to forecast litigation timelines and outcomes.

- Dan Rabinowitz explains that Pre/Dicta was developed over six years, with the initial product launching last year, focusing on behavioral analytics and data science.

- The product uses behavioral analytics and data science to predict litigation outcomes, including motions and time to particular outcomes, by analyzing judges’ proactivity, preferences, and biases.

- Dan emphasizes that Pre/Dicta’s tool is unique in forecasting case-specific outcomes rather than relying on generalized statistics.

How Pre/Dicta Helps Lawyers

- Dan Rabinowitz discusses how Pre/Dicta helps lawyers answer clients’ questions about the outcome of a case, focusing on the unique factors of each case.

- Pre/Dicta does not look at opposing counsel’s win-loss record or judges’ general motion grant rates but instead analyzes the specific parameters of the case, including parties, attorneys, and judges.

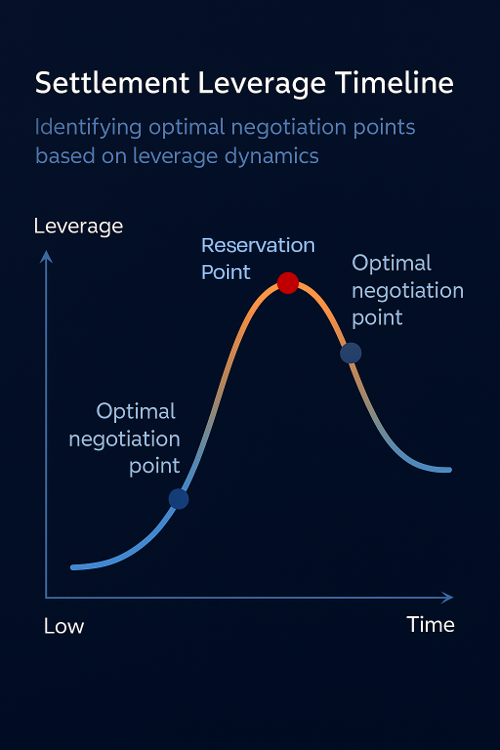

- Dan explains that winning in litigation is not binary and that Pre/Dicta provides nuanced predictions and forecasts, considering factors like time and cost.

- The tool helps lawyers strategize by providing insights into the likelihood of motions being granted or denied, which can inform settlement strategies and resource allocation.

Behavioral Analytics and Predictive Modeling

- Dan Rabinowitz elaborates on how Pre/Dicta uses behavioral analytics to predict judicial actions, focusing on judges’ past behavior and biographical characteristics.

- He explains that Pre/Dicta’s algorithm does not explain why judges rule a certain way but predicts their actions based on patterns and biases.

- The tool is designed to be intuitive for attorneys, providing clear and straightforward outputs without requiring them to manipulate data.

- Pre/Dicta’s output includes binary predictions (motion granted or denied) and numerical outputs (timelines for specific outcomes), helping lawyers make informed decisions.

Educating Attorneys on Predictive Analytics

- Speaker 1 inquires about the educational component for attorneys using Pre/Dicta, as many may not be familiar with predictive analytics or behavioral analysis.

- Dan Rabinowitz explains that Pre/Dicta’s tool is designed to be user-friendly, requiring attorneys to input only the case number, and the tool pulls all necessary information.

- The output is clear and straightforward, helping attorneys make strategic decisions without needing to become data scientists.

- Dan shares that a large firm has deployed Pre/Dicta extensively, with high usage rates and no help desk requests, demonstrating the tool’s ease of use.

Applications and Adoption of Pre/Dicta

- Dan Rabinowitz discusses the potential applications of Pre/Dicta, including risk assessment for insurers and litigation funders.

- He explains that Pre/Dicta’s tool is a risk assessment tool, helping companies make informed decisions about litigation strategy, budgeting, and resource allocation.

- Dan highlights that Pre/Dicta’s adoption follows a similar route as other technologies, with some firms and funders being more sophisticated in their use.

- He compares Pre/Dicta to other technologies that have transformed industries, emphasizing its potential to revolutionize the practice of law.

Dan Rabinowitz’s Background and Journey

- Speaker 1 asks Dan Rabinowitz about his background and how he transitioned from practicing law to developing Pre/Dicta.

- Dan shares his experiences at Sidley, the Department of Justice, and a data science company, where he developed an interest in data analytics and behavioral science.

- He explains that his experience in national security and understanding human behavior influenced his decision to apply behavioral analytics to the practice of law.

- Dan emphasizes the importance of thinking outside the box and leveraging advances in technology to improve the practice of law.

Challenges and Future of Pre/Dicta

- Dan Rabinowitz discusses the challenges of adopting new technologies in the legal industry and the importance of staying nimble and adaptable.

- He shares an anecdote about a partner who resisted adopting email, illustrating the resistance to change in the legal profession.

- Dan highlights the need for law firms to evolve and adopt new technologies to remain competitive and efficient.

- He expresses confidence in Pre/Dicta’s unique value proposition and its potential to transform the practice of law by providing accurate predictions and forecasts.

Conclusion and Final Thoughts

- Speaker 1 thanks Dan Rabinowitz for sharing his insights and experiences, expressing excitement about Pre/Dicta’s growth and impact on the legal industry.

- Dan Rabinowitz reciprocates the thanks, appreciating the opportunity to discuss Pre/Dicta and its potential.

- The conversation concludes with a reminder to visit the Pioneers and Pathfinders podcast website for show notes and more episodes.

SUMMARY KEYWORDS

law, behavioral analytics, attorney, judge, client, motion, practice, outcomes, fact, years, information, technology, data, company, litigation, denied, case, summary judgment, tool, factors

SPEAKERS

Dan Rabinowitz, Stephen Poor

Dan Rabinowitz 00:00

Thank you for the opportunity. Yeah, let’s start by talking about Pre/Dicta, your founder and CEO of the company these days, it’s a it’s a middle aged company, been around six years, not very long in the real world, but in the world of legal tech, that’s a long time. Yes, it is, although much of that was related to development, our product, which forecasts and predicts litigation outcomes ranging from motions to time to particular outcomes, was in development for a few years, and then we initially launched with a more limited product, and then, ultimately, last year, in November, we launched with the full suite that we have today, which uses behavioral analytics, data science, generally and particularly, looking at judges, proactivity preferences and biases to determine, as I mentioned, outcomes, both in terms of forecasting and predictions. So it’s fascinating description, and it’s a fascinating company and product. I’m a employment litigator by trade, or at least, used to be back in the day. How would I use I get a case that’s come in to me for a client, when the client’s first question is, what’s going to happen? Are we going to win? How does this tool help me answer that question in a specific case? Sure. So that’s exactly where it helps you. So unlike approaches of other platforms or services that are in the market that focus on more generalized statistics, we are interested in forecasting the outcome of your particular case based upon the unique factors that are present in your case. So we aren’t, for example, looking at the opposing counsel and their win loss record, or we aren’t looking at the judge and how frequently they grant motions in employment cases. Instead, we want to understand based on the unique parameters of your case, which include both the parties, the attorneys, as well as, of course, the judge. Because nothing happens in a vacuum. There’s actually a person, a human being, on the other side that has to make those decisions. So we look at those factors in order to come up with our predictions and forecasts. Now when your client is asking you that question. I presume that there’s actually a lot more wrapped up in that question than just it’s a superficial level. What they’re really asking is, well, of course, whether or not we’re going to win. But as we all know, when it comes to litigation, winning is ill defined or is not a binary answer, and that comes down to a number of different factors that are involved in any given case. So what you have are, of course, true win loss, right? So emotion is granted or denied, but then you have many other things, such as time, right? So how long, even if you win on summary judgment, how long will that take? And, of course, from the client perspective, they aren’t interested in it, from, you know, just period, like whether or not you’re going to be on vacation, the longer it takes, of course, the more it costs them to litigate, in terms of litigation costs. And then, of course, you know whether or not a particular motion might be denied is itself informative. So even if you’re coming to them and saying, for example, that my motion to dismiss will be denied, that doesn’t make you if you will look bad in the eyes of the client. In fact, it enables you to provide a very interesting or enables you to analyze a very interesting strategic question, which normally you can’t do, and that is whether or not we should file this motion to dismiss. Now, of course, many large firms always take the position, hey, we’re just going to file this. Maybe the judge doesn’t grant there, or maybe I’ve been before.

Stephen Poor 00:02

Hi. This is Steve poor, and you’re listening to pioneers and pathfinders. We’re joined today by Dan Rabinowitz, founder and CEO of Pre/Dicta, Pre/Dicta says it offers litigators AI tools that can forecast litigation timelines and provide accurate predictions for outcomes of motions. Dan has had many different roles in his legal journey. He started as a litigator at Sidley and later became a trial attorney at the US Department of Justice. He then served as general counsel at a data science company, and went on to be Associate General Counsel, Chief Privacy Officer and the director of fraud analytics for WellPoint military care. With all of these experiences, Dan took a deep interest in the innovation and technology side of legal work, wanting to focus on data analytics in particular, he ultimately decided to leave practice and develop Pre/Dicta. In today’s discussion, Dan speaks about the behavioral science factors that can help forecast legal outcomes. The information predictor provides lawyers in a given case, how he became involved with behavioral analytics and the need to think outside the box in the legal world. Thanks for listening in, Dan. How are you? It’s great you could make time to talk to talk to me today.

Dan Rabinowitz 01:21

I’m doing well. Thank you for the opportunity.

Stephen Poor 01:23

Yeah, let’s start by talking about Pre/Dicta, your founder and CEO of the company these days, it’s a it’s a middle aged company, been around six years, not very long in the real world, but in the world of legal tech, that’s a long time.

Dan Rabinowitz 01:38

Yes, it is, although much of that was related to development, our product, which forecasts and predicts litigation outcomes ranging from motions to time to particular outcomes, was in development for a few years, and then we initially launched with a more limited product, and then, ultimately, last year, in November, we launched with the full suite that we have today, which uses behavioral analytics, data science, generally and particularly, looking at judges, proactivity preferences and biases to determine, as I mentioned, outcomes, both in terms of forecasting and predictions.

Stephen Poor 02:21

So it’s fascinating description, and it’s a fascinating company and product. I’m a employment litigator by trade, or at least, used to be back in the day. How would I use I get a case that’s come in to me for a client, when the client’s first question is, what’s going to happen? Are we going to win? How does this tool help me answer that question in a specific case?

Dan Rabinowitz 02:47

Sure. So that’s exactly where it helps you. So unlike approaches of other platforms or services that are in the market that focus on more generalized statistics, we are interested in forecasting the outcome of your particular case based upon the unique factors that are present in your case. So we aren’t, for example, looking at the opposing counsel and their win loss record, or we aren’t looking at the judge and how frequently they grant motions in employment cases. Instead, we want to understand based on the unique parameters of your case, which include both the parties, the attorneys, as well as, of course, the judge. Because nothing happens in a vacuum. There’s actually a person, a human being, on the other side that has to make those decisions. So we look at those factors in order to come up with our predictions and forecasts. Now when your client is asking you that question. I presume that there’s actually a lot more wrapped up in that question than just it’s a superficial level. What they’re really asking is, well, of course, whether or not we’re going to win. But as we all know, when it comes to litigation, winning is ill defined or is not a binary answer, and that comes down to a number of different factors that are involved in any given case. So what you have are, of course, true win loss, right? So emotion is granted or denied, but then you have many other things, such as time, right? So how long, even if you win on summary judgment, how long will that take? And, of course, from the client perspective, they aren’t interested in it, from, you know, just period, like whether or not you’re going to be on vacation, the longer it takes, of course, the more it costs them to litigate, in terms of litigation costs. And then, of course, you know whether or not a particular motion might be denied is itself informative. So even if you’re coming to them and saying, for example, that my motion to dismiss will be denied, that doesn’t make you if you will look bad in the eyes of the client. In fact, it enables you to provide a very interesting or enables you to analyze a very interesting strategic question, which normally you can’t do, and that is whether or not we should file this motion to dismiss. Now, of course, many large firms always take the position, hey, we’re just going to file this. Maybe the judge doesn’t grant there, or maybe I’ve been before. This judge and the judge grants it well, if it turns out that in fact, you knew with absolute certainty, so setting aside predictor for just a moment, let’s assume you actually and setting aside any ethical concerns. You actually knew the clerk of the judge, and the clerk actually was the one that wrote, made the decisions, and wrote the opinions as it relates to motions to dismiss, and they and you sat down to lunch with them, and again, setting aside any ethical concerns for just a moment for this purpose of this exercise. And they said, I’m going to deny this motion. There is nothing you can put in here. I’ve already looked at the law. I’ve already looked at the facts. It doesn’t matter me. I’m going to deny the motion. Do you file it now? You could say, again, hey, let me just do this. This is part of big law practice. You know, in the grand scheme of things, not all that expensive. But of course, when you file that motion to dismiss, you’ve provided a roadmap to your opponents exactly where you see all the weaknesses of their case, and if you know that has zero benefit to you, in other words, you know it will be denied. You really have to think very hard. Should I do this? Should I be filing that and from a strategic perspective, if you have that information and your opponent doesn’t right, so plaintiff’s counsel hasn’t decided to purchase our technology for whatever reason, and you’re lucky enough to be among the more sophisticated law firms that has. So what do you do with that information you have, if you will, there is this knowledge and balance. So now plaintiff, of course, is litigated against large firms, and they know they’re going to file this motion to dismiss. Maybe they can start working on their discovery quest or so on and so forth. And you come back and you say, I’m filing the answer, and now off to the races on Discovery, and we’re going to push hard on Discovery. And plaintiff is blindsided by that. That puts you in a very potentially advantageous position to now push for a very reasonable settlement, or one that you might not have gotten earlier had you gone ahead through the long process. You know it’s going to take six, eight months a year and so on. So that’s just even if you knew that you were going to lose a motion, or again, if you knew that the motion for summary judgment would not necessarily be granted. So how does that affect your settlement strategy? So to go back to your question about win loss, our tool allows you, enables you to really make some very fine and very nuanced decisions and have discussions with the client around strategy that here that up to this point in time you really couldn’t do. And then, of course, to go back to the client’s question, the implicit question of, how long is this going to take, and how much money is this going to cost me to litigate, knowing, for example, that summary judgment will take a considerably longer time than you have a settlement offer today. That amount of time should be factored into whether or not you’re going to accept or negotiate around that settlement offer, right? So if plaintiff comes with a settlement offer fairly early in the case, and we can tell you if it does go to summary judgment and you believe you’re going to win, it’s going to take you another two and a half years. So now you can quantify what that means to the client. And you know this more than, of course, opposing counsel knows this, so that’s you know, when you would say, like, how you would deploy this. And the beauty of this is, because we don’t look at the facts of the law. We’re doing that behavioral analytics. We’re looking at the judge and the effect of all these other pieces on the judge. And of course, that has a higher degree of correlation than the facts in the law, right? Because the facts in the law don’t tell you how a judge will actually rule. It’s simply what you should put in your brief so that has a higher degree of correlation. So with that information, we aren’t beholden to eventual arguments you’re going to make or what law your associate is going to dig up. We can do all of this analysis the day that you enter your appearance. So that strategy memo is totally transformed.

Stephen Poor 08:19

So that’s that’s just fascinating to me. Let’s stick on the motion for summary judgment for a moment, because that’s where a lot of employment cases are resolved or not resolved. You’re not analyzing the facts or the law of a specific case. You’re analyzing behavioral analytics. Tell me what you mean by that. I’m not looking for any trade secrets, but help me understand what, what your product is doing, sure.

Dan Rabinowitz 08:43

So we sort of have to separate substance from predictions and forecasts. So when you’re trying to identify factors that can help you forecast or predict something, you’re not necessarily looking at the underlying issues at hand. So it could very well be, you know, like, if, if you think about, sometimes how certain instruments that people use in the financial markets, sometimes they’re not looking at the underlying security at all. They don’t really care about the, you know, how successful, or, you know, what that security, in terms of revenue or anything else is going to produce. Instead, they can look at factors that sit above that that provide them information as to what that ultimate value will be, and the value a lot of times, because you’re looking at from this a forecasting perspective, is divorce from the underlying asset, like the case of the in some financial instruments. So it’s the same here. When I say that we’re not looking at the facts and the law, the reason is not to indicate that the facts in the law are not important to the practice of law. Of course, they are. We’re not trying to be lawyers. We’re trying to be forecasters and predictors of what will occur. And for those characteristics, you don’t look at the facts in the law because those by themselves, don’t have a high degree of correlation with particular. Outcome, because you could think, and we all know this to be the case. Anyone that’s practiced law that you think you have the strongest case. You’ve spent years on this. You know the law backwards and forwards. In fact, you’re an expert in the law. You’ve written four books about this particular area of the law. You’re absolutely certain. You’ve spoken at dozens of conferences, written the law review articles, et cetera, et cetera. And you go before a judge and you make your argument now you are the expert on this, and you lose. Now, how is that possible? Because simply knowing the law doesn’t tell you your likelihood of success. Of course, it’s a factor in the likelihood of success. But if now you want to say, Okay, I want to sit back and say, If I had to predict what will happen next, what should I look at? So that’s where we came in. And we said, if you want to predict what will happen next, what we’re really saying is you want to predict what the judge will do, what action the judge will take next. To predict actions today, for the past 15 to 20 years, maybe even longer, we’ve been using something called behavioral analytics, which we analyze people’s past behavior and look for non obvious patterns, in other words, not directly associated, for example, with how many times they grant a motion, simply, but look at other factors around that motion, who the parties were, what types of attorneys were representing those parties, and then, of course, the unique biographical characteristic that every judge has, on the one hand, on the other hand, the non unique biographical characteristics that judges have. And what I mean by that is, while judges might seem very different, there’s a lot of characteristics that overlap, right? So what we can do is, you know, there are many judges, for example, that may have gone to a particular law school or practiced at a particular firm, or practiced for the government, so there’s going to be overlap between the hundreds and hundreds of judges. So with that overlap, there’s enough data that we can start seeing these patterns that can be tied to particular behavioral characteristics. Now the important caveat is is, I have no idea why it is that a judge born in the Midwest that went to a particular law school and, you know, has a particular net worth and worked in the government and so on and so forth, will rule a particular way. I don’t know that, and the algorithm doesn’t tell us that, but what the algorithm does tell us is how they will rule, how she will rule, and because, again, what we’re looking to do is not practice law. That’s why we don’t look at the facts in the law. I don’t need malpractice insurance, at least as it relates to the practice of law. Here we are looking to forecast and predict outcomes, and that’s why we sort of are able to divorce it from the law itself. And then, of course, that enables us to do something which is fairly unique, that we can operate independent of that analysis. Now of course, that also does not mean you ignore that analysis. So if we come to you and we say, look, the motion to dismiss will be granted or denied, or the motion for summary judgment is likely to be granted or denied, and then you go back, which you should as a practicing attorney, because what we do is we arm you with information. It’s not determined at all, because Pre/Dicta says it is a way it does not make it. So there are always exceptions to the rule, but that’s where you know, the attorney comes in and really does a deep dive and says, Okay, I have this particular data point and but I have other data points and how to weigh all these and how, you know, the attorney’s been involved in the case for four or five years, and they may have an understanding that we don’t. Now, again, we’ve tested this over millions of different cases, but nonetheless, there’s always going to be those outliers. There will always be those exceptions. So this is, if you will, arming an attorney in a way. If you think about the way that companies operate today, like the reason they bring a McKinsey in is the McKinsey can do the data analysis and provide a forecast. It doesn’t absolve the board or anyone else in the company of still doing the analysis. But if you want to apply the same approach that McKinsey does when they’re deciding on the health of a company or where a company might be in five years from now, they’re using predictive analytics. They’re using all these other all these other data science techniques that we’re essentially using, and we’re simply bringing that that’s generally used in the broader commercial context, and we’re bringing that into the practice of law. Fascinating.

Stephen Poor 13:54

So I’m getting to the education component for the attorneys, in terms of using the tool. Most attorneys aren’t going to have experience using predictive analytics or or behavioral analysis or the sophisticated tools, and I would think there would be a tendency to default to what the tool is telling them, or to default to their own judgment, when in fact, neither default is the right way of doing it. What’s the educational component of getting lawyers to use the tool effectively and efficiently.

Dan Rabinowitz 14:25

So when it came to the educational component, it’s something that I, you know, I used to practice law, and I gave it a lot of thought as to, how do we translate something that is really far into the practice of law, and then even if it wouldn’t be far into the practice of law, it’s still these are very complicated ideas, and how you deploy them, of course, is complicated now with that in mind. So first and foremost, when we developed the tool and the technology, we designed it that the attorney would not have to do anything other than tell us which case they want information about. So there’s no real. Manipulation of data on the attorney side, because attorneys don’t, they don’t give

Stephen Poor 15:03

you any facts, they don’t give you any law, they don’t give you anything other than just the case number, case

Dan Rabinowitz 15:08

number, and then with that information, as I said, because we’re doing a case specific analysis, we pull all the information that we need in order to create our predictions and forecasts. Now the reason for that is first and foremost, because we we are case specific. But then the reason that I really wanted to ensure that the output would be as clear as possible was because two reasons. First, attorneys are incredibly busy, and they don’t have time to become data scientists, so I didn’t want to provide them something that would then have to start filtering and manipulating and trying to understand, well, if I change this variable, what happens and so on and so forth. Instead, we spent all those years that I described originally, that puts us in the old man category, trying to figure out what techniques we should use to build the algorithmic models that the output is incredibly clean and straightforward. Now, what is the output? Now the output is comes in two formats. One is a binary prediction. So that binary prediction is simply the motion will be granted or the motion will be denied. Now, of course, how the attorney will go ahead and use that? They might use it in the way that I described before, knowing that their motion to dismiss might be denied. How does that affect the strategy of to file, push for settlement, push for early discovery, use that information that they withheld to deploy at a deposition and totally overwhelm the opposing side because they were blindsided by the fact that you were challenging one particular fact or one particular fact in the application of the law to it. So that’s, you know, one way that they can use that now when it comes to other aspects where we provide, for example, a numerical output. So let’s take the timeline feature. So the timeline feature, again, I didn’t want to just provide, on average, a judge takes, you know, 700 days to get to summary judgment, because that’s not really what the attorney wants to know. The attorney wants to know if I’m going to my client and saying, and the client asked for a budget for this year, or for the life cycle of the case. And I think that this will be resolved at summary judgment. I don’t want to know the average. I don’t want to know in generally in securities cases. Tell me if that’s the particular outcome, what is the effect on the time it takes for the case, or if it goes to trial, if that’s the outcome, because our timelines are outcome based, because no one really cares about the esoteric or the maybe academic question of like, how long does it take for a judge to rule on a pending motion? That’s not what you’re interested in. You’re interested in what is the effect of the outcome? The outcome is really what you’re most interested in. So each of the numbers that we provide a specific number, we’re not providing the mean, we’re the median. We’re providing a specific number of days it will take to arrive at summary judgment. And then, of course, for the attorney, the attorney now has to say, well, which of these outcomes is most likely? What am I going to discuss with the client? So then, in terms of educating the attorney, we actually have a client that did a very large deployment throughout the firm, and it’s a very, very large firm, and we have yet to receive, and I can tell you that they have a high rate of usage. We have yet to receive a single Help Desk request because they understand how to use the tool, because it’s intuitive. The output is intuitive, and then how they’re actually using it. I mean, I know how they’re using it. They’re using it to win business because they can go with a higher degree of certainty as to their estimates. So when the client asks, well, you’re telling me your estimate is 7 million, someone else came in with 5 million, or some discussion around that, they can say, Look, we base this on a tool that analyzed 15 years of case data and that analyzed literally millions of cases to get to this idea of how long this will take, and therefore our estimate is tied to actual data, or they can use it when a class certification motion is pending and they’re on the other side of that, and they have a settlement offer from plaintiff, they can advise their client that says, Look, you could have confidence in the fact that Pre/Dicta says it’s going to be denied, and therefore don’t settle prematurely. That can literally cost you millions and millions of dollars. So because the output is so obvious, it’s then for the attorney to decide how to deploy that strategically. And while we can come up with certain strategies, and we’ve frankly, been informed by how our clients have used it, we can only think of so many usages. But of course, people that are actually litigating in the trenches come up with even more uses, and it’s really just taking a step back, as you would imagine, with any new technology that’s being deployed in the law, there are going to be users or potential users that are more sophisticated and amenable to trying to use every opportunity or every technology in this particular instance to their benefit. Now, of course, that has to be balanced with the fact that there are any number of technologies that are pitched because they’re the latest and greatest. And if you go back, I’m sure you go back 345, years ago, and there was some technology that everyone thought was going to be transformative, and then either did it apply to the particular practice of law, or it just didn’t live up to the,

Stephen Poor 19:57

oh, you’re talking about blockchain. Yeah. And any number of different

Dan Rabinowitz 20:01

ones you can go to. But the nice thing here is, is that we designed this to be highly focused on an area of the law that everyone wants to know, and that is, what will the judge do. And legal research, traditional legal research, doesn’t get you there. And because, unlike other technologies, we are simply people translating a technology that existed in the open market had had been validated and as trustworthy and had already seen huge benefits for the other sectors that it was being deployed in. So of course, some attorneys will bristle at the idea that technology can decide or can provide any insight into, you know, outcomes of judges, but you had the same issue with doctors many years ago cancer diagnoses. There were numerous studies that showed because cancer diagnoses, in a way, is a repeatable event, just like a piece of litigation. Now, of course, there are different factors. Everyone. Everyone has slightly different biological makeup, different medical history. The cancer might present itself slightly differently, but when you look at a massive data set, many of those things will be repeated, not maybe not one to one, but, you know, maybe a 90% match year and a 70% match year and so on and so forth. And when they did test to try to determine whether or not a predictive analytics system was better at actually diagnosing cancer correctly against doctors and practitioners, some of again, who might be the world’s experts. There’s no question that Predictive Analytics does a better job. Now, it took doctors a little bit to get there, but it also they’re still for better, for worse, they’re still cancer doctors. It hasn’t taken away the need. It simply allows them number one to second opinion, if you will, immediately, and then also allows them to focus on the aspects of cancer treatment that they should be spending their time on. If something else can do something on your behalf better than you can, why would you try to enter that particular space? Why would you, put it very bluntly, waste your time, especially when you’re an attorney or a doctor, where for the most part, you’re being you know your value a lot is tied to the amount of time that you can spend on any given matter.

Stephen Poor 22:05

I would think that insurers would be a good customer base for you that this, this seems to play right into litigation, insurers specifically, but general insurance companies that are insuring against risk of litigation.

Dan Rabinowitz 22:20

Yes exactly one of the ways that you might look at the tool, you know, from a broader perspective, is simply it’s a risk assessment tool. So of course, how attorneys might use that is in terms of strategy, in terms of budgeting, in terms of resource allocation, but certainly on some level, this is a risk assessment tool. And companies that operate within the legal space and operate not necessarily from from a practitioner’s perspective, but from a risk perspective. Insurers are absolutely part of our client. In other words, our client profile our insurers. Then of course, you have others, although a little bit less so to be honest, because mainly they’re controlled by attorneys, and that is litigation funders. So straight litigation funders, where you still have a lot of attorneys involved. For us, we see in terms of adoption, it’s a very similar route of adoption that we have within firms, but then you have secondary funders that are removed, much like in the financial example that we were talking about earlier, where they’re less interested and they’re less invested, if you will, in the nitty gritty of the law, and they’re much more invested from a financial risk and a financial modeling perspective. They of course, appreciate any tool that will provide a more objective and data based risk assessment.

Stephen Poor 23:33

So let’s talk a little bit about your background. You go to Georgetown, you get out of law school, you go to work for a fine law firm as a litigator, at some point you become involved in this incredibly sophisticated data analytics, behavioral analytics, and that’s not a typical path for a young law student. How? How did that? How did that turn happen?

Dan Rabinowitz 23:54

Yeah, so I mean, I had a lot of great experiences, especially being in the DC area. So you mentioned practicing at a world class law firm and getting to work at the Department of Justice and then at a very sophisticated government contractor. All those are great. But what I also realized after I’d been exposed to data analytics and specifically the idea that today, the way we understand people is very different than we used to. So I was working at a company that, in part, what they their service offering had to do with how do you understand what particular actors will or not do, and this was in the national security context, so very important well, to take nothing away from the importance of litigation, obviously national security interests, and trying to figure out precisely whether or not a particular person or entity is a threat is key. Now, of course, there’s human intelligence, and you know the more traditional ways that that we’ve made those assessments, but if you think about how it’s done today, and on the mass scale that it’s done and you know how we’re able to identify those that has a lot to do with this behavioral analytics, it has a lot to do with crunch. Using massive amounts of data, looking at different, non obvious factors that might ultimately have a high degree of correlation with a particular outcome that you might be very concerned with. So understanding that particular use case, I recognized and and I thought back to when I was, you know, a young associate, and I was actually tasked specifically once to figure out, if you will, to predict on behalf of the client. Write a memo and tell us not what the law says. So not one of the you know General tell us, you know we’re asserting a particular cause of action. Apply the facts to that. Go back and do the research and whatever jurisdiction we might be in. But specifically to look at the judge and say it was in a products case, we have a product liability case, we have a motion to dismiss pending. Look at the judge’s decisions and see what can we tell the client about the likelihood that this particular judge and how they’ll rule on our motion. When you go back and look at the data, there’s maybe a handful of published decisions having to do with the motions to dismiss, despite the fact that a judge might hear any number in a given week, most of those are not published decisions. Most of those are just simply, you know, one sentence orders. So you know, you’re asked to do something as a young associate, you go ahead and do it, pull up the number of cases. There’s only 10, as I said, five or 10, none of which are in the products context. So, you know, having that experience. And then, of course, we still have to make the client happy. So we did draft a memo based on the information that we had at hand, and maybe did some other comparisons in order to fill the empty space, if you will. But now understanding that we had developed far beyond that, and when you think about where technology has gone, setting aside for just a moment, like in the last year or two, with generative AI, but if you look at the past 20 years, technology has developed by leaps and bounds, whether it be from taking a phone that is more powerful than a computer that you ever had 15 years ago to any number of different advances that we have when it comes to the law, most of the advances have been limited to ediscovery and a couple of other spaces, none of which really represent a tremendous leap, you know, and if you think about it in many ways, it’s actually almost regressive. It used to be, if you will, that discovery, in terms of the volume, was much smaller than it was today. Now, part of that is because we operate in a digital world, but also part of that, one assumes, is at least partially driven by the eDiscovery and the sophistication we have to analyze so many documents. So if anything, it’s actually created in some ways more of a mess or more of an issue. But then you think about all the other areas that in the practice of law, that most of those have remained untouched, untouched by all these advances in technology. So there has to be room for additional advances, additional ways that we can apply other areas or other advances in the commercial context, and apply it to the law. I mean, I operate, I do many different things, one of which is also a book collector. And I have like, five or 6000 books. And when you’re collecting books, I always viewed it as part of the exercise of dealing with that amount of information is category and classification. Now the most fruitful areas of my research have always been where you’re looking at a cross discipline, right? So you might be looking at one area that’s unrelated to the history of what you are currently interested but that is so informative, even though it comes, if you will, out of left field. So deciding to take the information that you have for behavioral analytics that have been applied in any of these other contexts, and then saying, hey, the judge is a human being, just like we’re humans that Google can profile us and tell us what we’re going to buy next, the judge is equally a human being. We just need to think out of the box within the law. We need to be more open to ideas that advances in other areas can and certainly will in the future have tremendous impact on the practice of law, even though they seem divorced from the practice of law. Mean, all of this changes over a period of time. And you know, to go back to a bit to what we were talking about, about adoption, about enabling adoption, that’s really what you see, that people are more interested today in trying to be a bit more nimble. You know, everyone has the apocryphal story about the partner that you know, when email first came out, he would have his assistant printed out, and then he would write a response, and then they would, you know, type it up, and then email it on their behalf.

Stephen Poor 29:12

I don’t remember that being apocryphal. I remember that real example,

Dan Rabinowitz 29:17

yes, yeah, yes. Everyone, I’m sure has that story, but you know, at the end of the day, that’s that’s impossible now, and when you look at the business of law and you look at how many firms have revenue that far exceeds many major companies, and they have employees on a scale that was unheard of, and how the law firm as a business has had to adapt to that having, you know, entire functions that they never thought they would have to bring in house, right? How do you manage? You know, when you have 30 offices and 5000 attorneys and so on and so forth, and revenue and clients all over the world and tax, they’re just so it gets so complex that you’ve now turned. The business of law into, you know, more or less into a regular corporation. And things that corporations have had to deal with, and law firms have had to continue to move in that direction. And law firms that have been unable to do that you’ve seen over and over again, either they become targets for acquisition, or they go out of business, just like any other commercial industry, right, where you have advances and you and someone doesn’t keep up, that’s what you see happen. So, you know, here, there’s, you know, when, when I sort of went down this path. I also realized that, well, to me, it seems obvious a lot of times, what seems obvious to one person is not obvious to the next. And needless to say, the first person I pitched my technology to did not buy it, despite the fact that I think has an obvious value. Nonetheless, when, when I was contemplating going back into the law, after had a brief break to write a book, I thought about going back to practice, to be frank and DC, even if I would like to think I’m a I’m a good lawyer, DC is blessed with many good lawyers, tremendous number of great lawyers, even exceptional lawyers. And I thought, well, I have this idea that seems to be untapped in the law, and seems to get at an area that is incredibly important to the practice of law, but is not within the practice of law. Let’s see if I can’t build something around that. And I found a partner, and we’ve been able to take it to where we we have today, which I’m very proud of that. Well, I can’t say I’m unique in terms of my ability to practice law. I believe that we are unique in terms of our ability to predict and forecast litigation outcomes.

Stephen Poor 31:35

Well, it’s certainly a fascinating company, a fascinating area, and I really appreciate you spending the time talking to us about it and sharing your views. It’ll be great to continue to watch the growth of the company and how you can continue to make practice better for clients and for and for lawyers. Thanks for sharing Absolutely.

Dan Rabinowitz 31:55

Thank you again for having me on it’s been a fascinating discussion.

Stephen Poor 32:00

Thanks for listening to pioneers and pathfinders. Be sure to visit the Pioneer podcast.com For show notes and more episodes, and don’t forget to subscribe to our podcast on your favorite platform. You.